The Future of People, Planet, and Profit

Capitalism and the financial markets are not yet structured to financially reward companies who do good in the world. This is the central problem with our economy that we will need to solve.

In 1970, legendary economist Milton Friedman published his seminal essay, The Friedman Doctrine, in the New York Times declaring that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”

The Friedman Doctrine became the north star for generations of corporate managers from B-Schools to board rooms and ushered in a new era of Gordon Gecko style, “Greed is Good,” capitalism where corporations unabashedly made money hand over fist. The maniacal focus on profits created lots of wealth but also caused collateral damage in the form of significant income inequality, environmental harm (ex: the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill), corporate fraud (ex: Enron), and public health disasters (ex: Purdue’s Opioid Crisis).

Even as prominent business leaders over the past few decades have begun to shift away from the Friedman Doctrine and toward something that vaguely resembles Stakeholder Capitalism, where people and planet are viewed as equal, if not bigger priorities to profit, the global economy still primarily operates under the vestiges of Friedman’s Doctrine.

Novel purpose-driven corporate trust structures like what Patagonia adopted in 2022 or the broader B-Corp movement are ways to enforce responsible corporate behavior, but with only 6,000 B-Corps in existence today worldwide, there’s a lot of progress yet to be made. On a more mainstream level, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) campaigns and Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG) frameworks are two more approaches that companies have taken to try and balance profits and purpose. CSR and ESG are well-meaning steps in the right direction but both are deeply flawed and have much to improve upon to be effective in the long run. ESG investing especially has become a divisive issue in financial and political circles, with the left complaining that ESG is ineffective greenwashing and the right denouncing ESG as radical leftist wokeism that violates the sacred fiduciary duty to just make money for shareholders.

To be clear, I am not categorically against B-Corps, CSR, or ESG initiatives. I believe that companies and investors should be doing much more to ensure they are responsible and respectful of the planet and the societies they interact with. I do not think that profit should be the only thing a company needs to optimize for and that social and environmental good should be baked into every corporate charter. Those who criticize ESG as hijacking corporations to promote political causes are in denial that the actions of companies have any effect on the world outside of the product or service they sell. An airline company is not just a profit generating machine, it’s also a carbon belching, fossil fuel guzzling machine that affects the world beyond the profits it creates.

Regardless of how far companies have come with these purpose driven activities, corporate programs that emphasize environmental and social goals are typically viewed as cost centers, not profit centers. Meaning, when profits are up, these programs can thrive, but when profits are down, these programs are typically the first to disappear as the company doubles down on improving the bottom line. Making profit is an existential imperative for companies, hitting its ESG goals is not. To a Friedman Doctrine style corporation, the bottom line is still the bottom line and everything else is expendable.

The Friedman Doctrine in Action

No matter how well you’re doing with your ESG activities, profit is still the central focus of how a company’s shareholders measure success because that’s the way the predominant capitalist system is hard-wired. A company’s share price is essentially a single number that reflects how the world feels about a company’s value. All of the complexity, effort, and sacrifice associated with operating a company is distilled into that one number. That’s like learning the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe, and everything is simply, the number “42.”

I cannot think of any environmental or social progress metric that has a meaningful effect on a company’s share price, assuming it hasn’t broken the law. The markets almost never react when those things are reported by companies. Companies have been publicly reporting on their sustainability and social justice performance for a while now, but you never see a stock price rocketing to the moon because the company just announced record levels of atmospheric carbon being captured, unless the company’s main business model is earning money by capturing carbon.

C-Suite executives who are primarily compensated in their company’s stock are strongly motivated to optimize their operations for profit. Profits are a means to the end of a higher share price with a bigger bonus for them to take home. This can create profit myopia for managers at companies but also for investors of all kinds, from big institutional funds to elderly retirees looking to grow and preserve their retirement funds.

Let’s imagine a fictitious food company that happens to abide by strong ESG values. We’ll call it AnyCorp Foods. AnyCorp makes a lot of money, but they also try to do good in the world. But like most companies, the C-Suite and shareholders are all rewarded handsomely if profits and the share price go up.

While the CEO of AnyCorp Foods may not have their bonus tied to how much carbon their company sequestered or the level of workplace diversity they have, they are at least ideally aware of their company’s efforts to make those ESG values happen. The CEO can at minimum tap into their conscience and do some good in the world and build a nice PR narrative that their company is a good global citizen, even though their salary isn’t directly tied to those actions that benefit the planet and society.

But AnyCorp’s CEO isn’t the only one whose income is based on the company’s share price. Enter Ms. Carroll, a public school teacher in Texas who’s 5 years away from retirement and indirectly owns shares of AnyCorp through her pension fund. Of course, Ms. Carroll didn’t buy those shares directly. A hedge fund in Connecticut that manages the pension funds for all public teachers in Texas used that money to buy a big chunk of AnyCorp’s stock. That hedge fund has a fiduciary duty to the teachers and will only make investments that have a good chance of earning profit.

This connection between AnyCorp Foods, the hedge fund, and Ms. Carroll is commonplace and illustrates how profit motives can quickly crowd out society benefitting ones in the financial markets. Even though AnyCorp’s CEO has done a great job building up initiatives that help save the planet and treat people fairly, Ms. Carroll and the hedge fund working on her behalf simply see AnyCorp Foods as a profit making widget. The hedge fund manager wants their annual bonus and Ms. Carroll simply wants to retire with a nice nest egg. And even though they both as individuals support altruistic planetary and societal causes, they’re forced into an invisible dance of fiduciary duty to make sure AnyCorp is only focusing on profit, not the environment or society.

In real life, the Teacher Retirement System of Texas actually divested a portion of its $173 billion pension fund from investment companies like BlackRock who boycotted oil and gas industry stocks as part of their ESG investing strategies.

The hedge fund and other big investors can do a lot to influence who is running the company if they don’t approve on the direction its heading. After a few bad quarters of financial performance the hedge fund starts to wonder why AnyCorp is spending so much time and money on altruistic causes and not devoting those resources to improving profits. Since the hedge fund owns a lot of AnyCorp shares, they can stage a coup and clear out existing management and place new people at the helm to eliminate the ESG stuff and get back to generating profit (this also happens in real life).

For all intents and purposes, Ms. Carroll’s needs are the biggest priority in this relationship chain, and she knows she can’t pay for her retirement expenses with the carbon that AnyCorp sequestered as part of their ESG initiatives. Unbeknownst to her, her needs set off a chain reaction of decision making and incentive structures in the financial markets that ultimately puts AnyCorp’s CEO out of a job for focusing too much on making the world a better place. Despite living in different worlds, the teacher, the hedge fund, and the company are all bonded by their pursuit of profit, not the well-being of people and planet. This is the Friedman Doctrine in action.

Who is to blame? No one, yet everyone. That’s just the way the system is set up right now and everyone is just doing their job within it. There’s perfect diffusion of responsibility here where no one really feels responsible for how the system is set up and corporate managers just tell each other, “this is the way it’s always been done” over and over again until we all die.

It’s hard to disagree with someone for simply wanting to live comfortably and have their hard earned savings preserved. But the system doesn’t allow for any corporation to spend a significant amount on purpose-driven activities at the expense of profit over the long run. It ignores the fact that companies have a very big impact on the community and the planet and relegates them to profit making machines, despite what any progressive CEO may tell the public.

Capitalism and the financial markets are not yet structured to financially reward companies who do good in the world. This is the central problem with our economy that we will need to solve in the decades ahead.

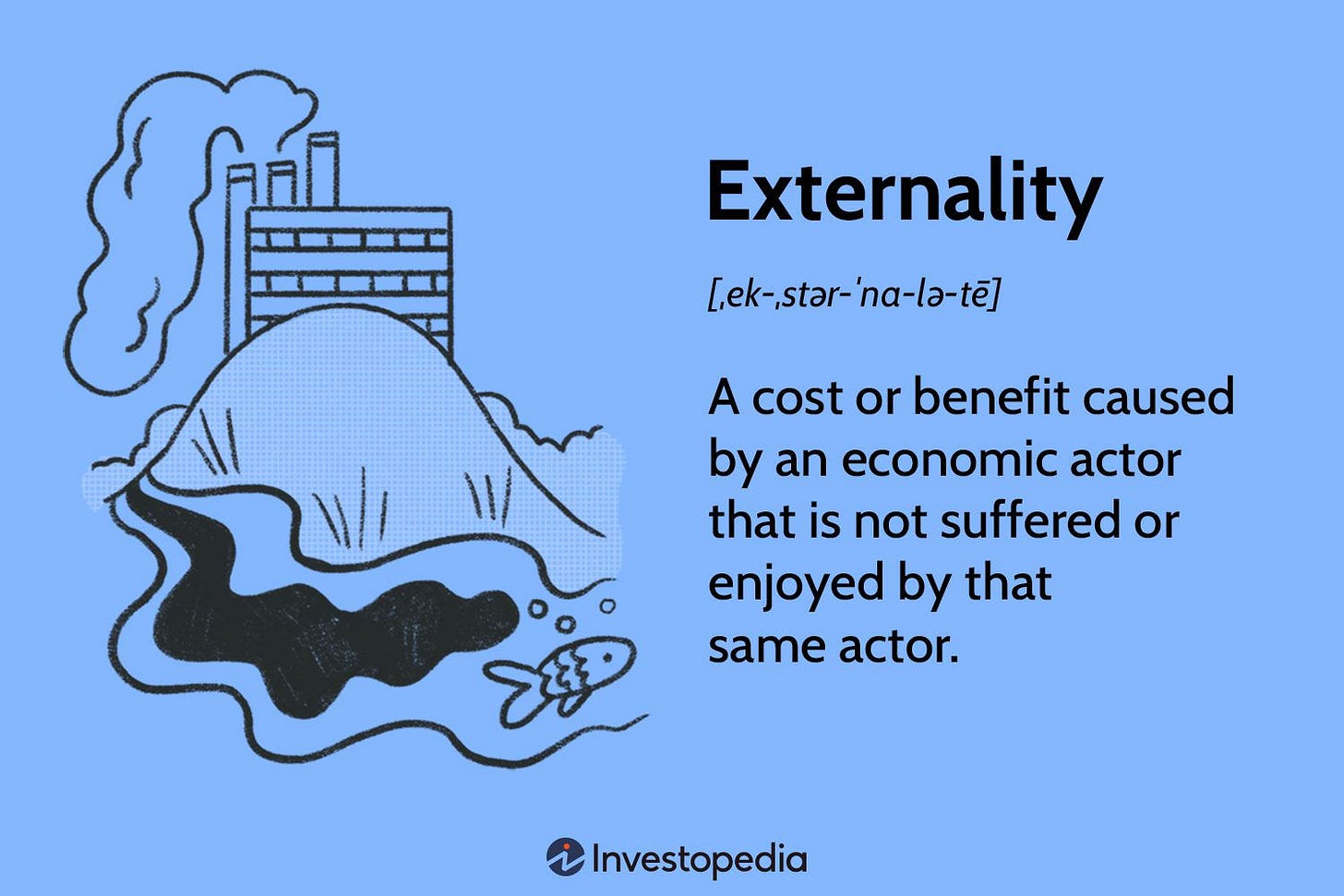

Measuring Corporate Externalities

The solution to getting companies to prioritize profit and impact may come down to something as dry as enhancing accounting practices. Money is pretty easy to measure. Externalities like pollution and social injustice are much harder to measure relative to money. And since money has been the default language of commerce from the beginning, it’s up to us to translate the impact of externalities into financial terms that are compatible with how the rest of the economy works. Even the word “externality” implies that these issues are “external” to the business, as if the corporation is shielded from issues of people and planet as it concerns itself with only the things “internal” to its operations.

Measuring and calculating financial value on the health of the planet is not a new idea. Thankfully, there are many working on this problem so that something like the health of a rainforest can at least be represented by a number on a company income statement alongside revenue and expenses. This is a challenging task. And not only is the process of measuring one kind of externality difficult, there are a multitude of them and the metrics for measuring soil health are wildly different than the metrics to measure factory working conditions or water quality.

But just because something is hard to do is no excuse to not do it. Organizations and initiatives like the Intrinsic Exchange Group, Natural Asset Companies, and the Regen Network are all taking their own approaches to measuring and assigning monetary value to natural resources ecosystem services that previously had no specific dollar amount attached to them. Financial accounting frameworks like SASB Standards aim to establish generally accepted methods by which those externalities are valued, which enables more efficient and true markets to form around those things.

I am rooting for all of these organizations and others like them who comprise the movement to account for externalities so that one day they cease to be called “externalities” and are just seen as one of the many essential costs and benefits of doing business. You cannot manage what you cannot measure and today we are at the stage of figuring out how to measure human and planetary well-being in a language compatible with the capitalist system we find ourselves in. This work is ultimately enabling Ms. Carroll to one day root for AnyCorp to save the planet because not because it’s the right thing to do, but because it’ll help raise AnyCorp’s share price and give her a bigger pension.

If we can get the outcomes of people, planet, and profit to speak the same language, then we can change the capitalist system so that corporations are intrinsically motivated to improve them all at the same time. I hope one day we can hear a CEO announce how much carbon they sequestered that quarter and have the share price jump up immediately. And if that happens, that’ll mean that the financial markets will finally have a way to value and improve the state of the environment and society.

It’s Valuable Because We Say It Is

All of this comes down to the question of what society values. The US Dollar is worth what it’s worth because a critical mass of people on the planet have all agreed that that’s what it’s worth. People can easily trade with each other because there is mutual understanding of what a particular currency is worth and that’s one of the things that makes the economy work.

We must remind ourselves that financial value is a human construct that relies on pure belief. Because value is based on human feelings, it isn’t always logical. How can an Hermès Birkin Bag, which has absolutely no value for sustaining life, be worth $500,000, while a bottle of water, which is absolutely necessary for life, costs only $1? Scarcity, sure. But those prices are the way they are because there’s enough people in the market who will agree to pay those prices, even though the prices don’t necessarily correlate with the true usefulness of the items. Price and value are not the same.

I think most individuals agree on some level that environmental and societal well-being has value. I also think very few, if any, individuals would be able to tell you in dollar amounts what that value is. Maybe some things should be impossible to price. Like, how much is your family worth to you in dollars? You simply can’t answer that.

The problem with Capitalism is that if something doesn’t have a price, it can’t be properly represented in the system. A thing without a price that exists in a capitalist system is like showing up to a party and not being allowed to speak or even have a name.

Capitalism has objectively been one of the most effective, and very flawed, tools that humans have created to build things. But for better or worse, a lot of us on Earth are living within it. And barring an overnight economic revolution of epic proportions, it’s probably going to be here for a while longer.

Do we simply throw our hands into the air and let Friedman reign? Friedman tells us to let companies do whatever they need to do within the law to make profit, then the shareholders can cash those checks and donate to nonprofit causes as individuals in order to undo the environmental and societal harm that those companies may have inflicted in pursuit of profit.

Here’s Friedman in his own words on that topic…

“Of course, the corporate executive is also a person in his own right. As a person, he may have many other responsibilities that he recognizes or assumes voluntarily—to his family, his conscience, his feelings of charity, his church, his clubs, his city, his country.

He may feel impelled by these responsibilities to devote part of his income to causes he regards as worthy, to refuse to work for particular corporations, even to leave his job, for example, to join his country's armed forces. If we wish, we may refer to some of these responsibilities as ‘social responsibilities.’

But in these respects he is acting as a principal, not an agent; he is spending his own money or time or energy, not the money of his employers or the time or energy he has contracted to devote to their purposes. If these are ‘social responsibilities,’ they are the social responsibilities of individuals, not of business.”

But passing the social responsibility buck from companies to individuals feels inefficient, ineffective, and even condescending. It’s like how Starbucks will eliminate plastic straws for its customers, asking them to “do their part,” but the company still gets to use giant plastic cups and tons of other plastics behind the scenes.

Why can’t we have companies do the right thing in the first place so we don’t need all those nonprofits fixing things after the fact?

Are we ok as a society with Friedman suggesting that Purdue Pharma should make as much profit as possible, create an opioid epidemic in the process, then rely on the slightly richer shareholders of Purdue stock to donate—as individuals—to a nonprofit opioid treatment clinic? How much share price appreciation is enough to bring back the thousands of people who lost their lives to opioids?

Until we find a way to attach financial value to corporate externalities and make it a fiduciary duty to improve people, planet, and profit, the ghost of Milton Friedman will continue to haunt us all.

Nice narrative. As a 63 yr. old Black American, first generation university grad., Ivy League, I am well aware of how the dynamic duo --Freeman and Reagan, sent America down the corporate-greed rabbit hole. Unfortunately, I don't see it being changed anytime soon.